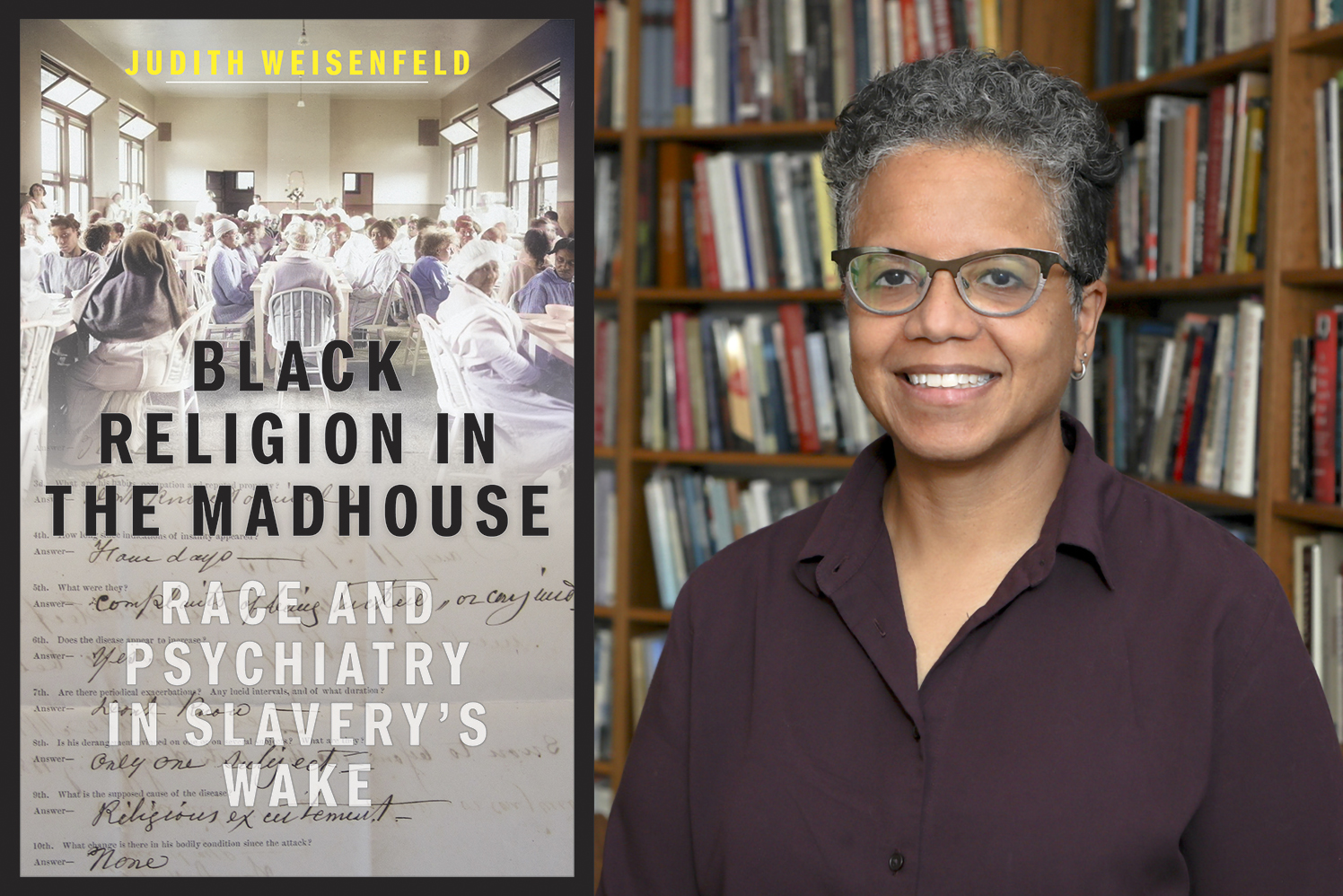

Now Reading: Author Judith Weisenfeld unpacks historic links between religion, race and psychiatry

-

01

Author Judith Weisenfeld unpacks historic links between religion, race and psychiatry

Author Judith Weisenfeld unpacks historic links between religion, race and psychiatry

Princeton University researcher Judith Weisenfeld has delved into the connection between religion, race, and psychiatry in America. In her recent work, “Black Religion in the Madhouse: Race and Psychiatry in Slavery’s Wake,” she reveals the prevalence of attributing mental illnesses to religious causes among African Americans in mental hospitals during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Weisenfeld, 59, faced the challenge of examining a wide range of literature, including psychiatric studies, records from hospitals and courts, and newspaper articles for her book. She was determined to shed light on the stories of individuals who were labeled as mentally ill due to superstitious or overly emotional behavior and ended up in institutions where they lived, worked, and sometimes died.

Reflecting on the racist psychiatric theories of the 19th century, Weisenfeld highlighted how these ideas were used post-slavery to maintain structures that subjugated Black individuals. She emphasized the role of medicine in pathologizing aspects of Black community, connection, and survival.

Weisenfeld, who does not identify with any religion, discussed with RNS the perspectives of psychiatrists from different racial backgrounds towards evaluating Black individuals around the turn of the 19th century, as well as how Black religious leaders then and now address mental health issues.

The book explores the treatment of Black individuals in state mental hospitals, particularly how their religion and race influenced their care. Weisenfeld noted that white authorities often viewed African American religion as a factor contributing to mental disorders, rather than considering patients as individuals.

Reports from that era frequently mentioned “religious excitement” as a reason for mental illness among Black Americans. This term referred to mania or agitation, with white psychiatrists associating it more with Black individuals by the late 19th century.

Weisenfeld highlighted that early white psychiatrists treating Black patients were often religious themselves, with ties to Protestant denominations. She emphasized their role in pathologizing African American religious practices while promoting their own beliefs as morally and mentally beneficial.

Regarding the response of Black religious leaders to the increasing diagnosis of mental illness linked to religious excitement, Weisenfeld noted that they had concerns about how these practices were perceived and sometimes worked to reform them. They resisted the idea that such practices were pathological manifestations of Black religion.

The researcher also touched on examples of religious excitement, including practices rooted in African traditions, such as hoodoo and conjure, which were often misunderstood by the medical establishment as superstition and mental illness.

Weisenfeld described the disheartening nature of her research, especially when reading about individuals who spent years in mental institutions and ultimately died there. However, she found hope in newer movements that aim to reshape theories and practices in addressing mental health issues related to race and religion.

In conclusion, Weisenfeld’s work seeks to provide insights for religious leaders, medical professionals, and other authorities to reconsider assumptions and legacies from the history she explores, which dates back to the late 19th century.