Now Reading: Turbulence at the Airport

-

01

Turbulence at the Airport

Turbulence at the Airport

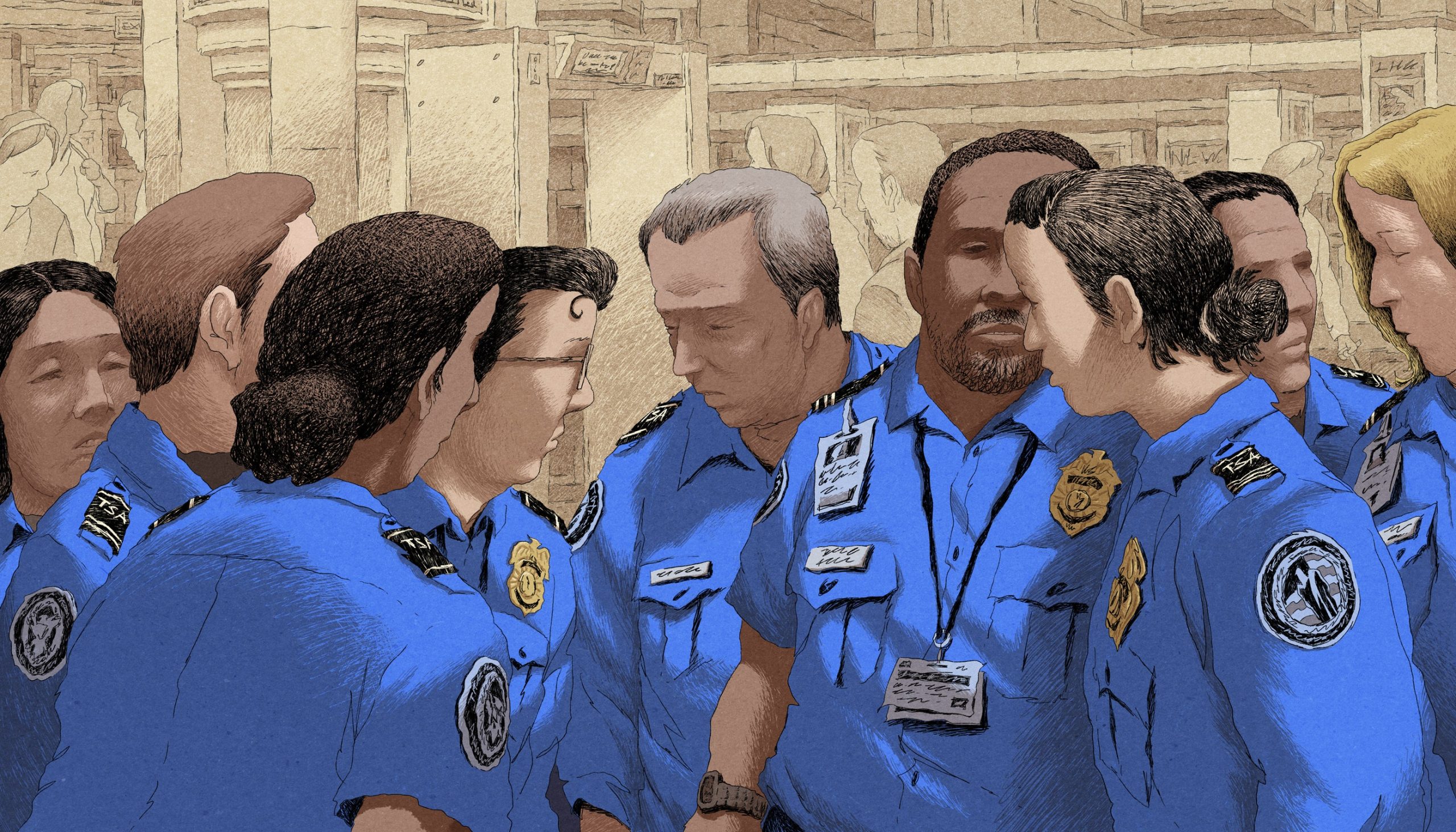

When Juan started working for the Transportation Security Administration, or T.S.A., around seven years ago, he had doubts about his future there. He was assigned to handle the screening checkpoint and inspect bags at Palm Springs International Airport, located near the San Jacinto Mountains, a few hours’ drive east of Los Angeles. He had hoped that a federal government position would offer stability and a livable wage, but he only received part-time hours. His pay was so low that he had to live with his parents and take on a second job. His supervisors seemed quick to reprimand him for minor mistakes. He expressed frustration at all the troubles he faced just to be a “meat shield.” Juan, whose real name is withheld for privacy, underwent training both in Palm Springs and at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Georgia, where he interacted with Border Patrol agents, corrections officers, and F.B.I. officers. Even in those settings, the T.S.A. was viewed as a somewhat neglected agency, according to Juan.

Juan was a young child when the T.S.A. was established as part of the response to 9/11 during the George W. Bush Administration. By the fall of 2002, approximately fifty-five thousand transportation security officers, or T.S.O.s, were screening passengers for the T.S.A. Initially, they were private contractors but later became federal employees, and in 2003, the T.S.A. became part of the Department of Homeland Security. Despite the agency’s efforts to enhance air travel security, it often receives criticism for causing inconvenience. The role of T.S.O.s in intercepting firearms and preventing security threats like the attempted “shoe bomb” incident after 9/11 showcases their dedication to maintaining safety.

Even after the T.S.A. was incorporated into the Department of Homeland Security, its employees had fewer rights compared to other federal workers. T.S.O.s were unable to collectively bargain, and their wages and benefits were closer to those in industries like fast food and retail rather than the general federal pay scale. This disparity contributed to a dissatisfied workforce, which affected the agency’s public image. After facing challenges, including a government shutdown and the pandemic, changes were made to improve the rights and pay of T.S.O.s, bringing them closer to other federal employees’ compensation levels.

In recent times, the T.S.O. union negotiated a collective-bargaining agreement benefiting T.S.O.s and enhancing their rights. However, a shift in leadership at the T.S.A. under the Trump Administration led to unfavorable changes for the workforce, including the nullification of the union contract. This decision left T.S.O.s feeling uncertain about their job security and facing new restrictions and disciplinary measures at work.

Despite the challenges, Juan and his colleagues continue to carry out their duties diligently, maintaining a balance between security and customer service. They navigate various situations at the airport, ensuring safety while dealing with demanding passengers and evolving security protocols. The uncertain future of the T.S.A. and the impact of potential changes on the workforce have created anxiety among employees like Juan.